One of the most incredible aspects of Chile is that a good part of its northern territories, in addition to being known for its scenic beauty and therefore a renowned tourist destination, represents a real economic banner for the entire country thanks to the enormous mineral and metal resources that distinguish it. Metals and minerals, two realities that already in the second half of the nineteenth century had begun to attract European minds in search of fortune and ready to exploit the mining potential of many areas of the Atacama desert. Since those days, when the fortune of the mining industry revolved around saltpetre, things have not changed. The extraction of many minerals and metals continues to represent one of the main economic sources of the country. In addition to iron, molybdenum, lead, zinc, gold, silver and coal, the extraction of which is still widespread in the southern part of the country, there are two metals that occupy most of the Chilean mining activities. I am talking about Copper, of which Chile is the first producer in the world, and Lithium, of which the country holds the export record. About one third of the national GDP derives from the extraction, production and export of metals and minerals. With 8 million tons, Chile has the largest lithium reserves known to date, then comes Australia, which with 2.7 million tons holds the record for production, Argentina with 2 million and China with 1 million. The magnificent colors of the Atacama Desert therefore hide an enormous mineral potential, almost 30% of the world’s estimated lithium reserves.

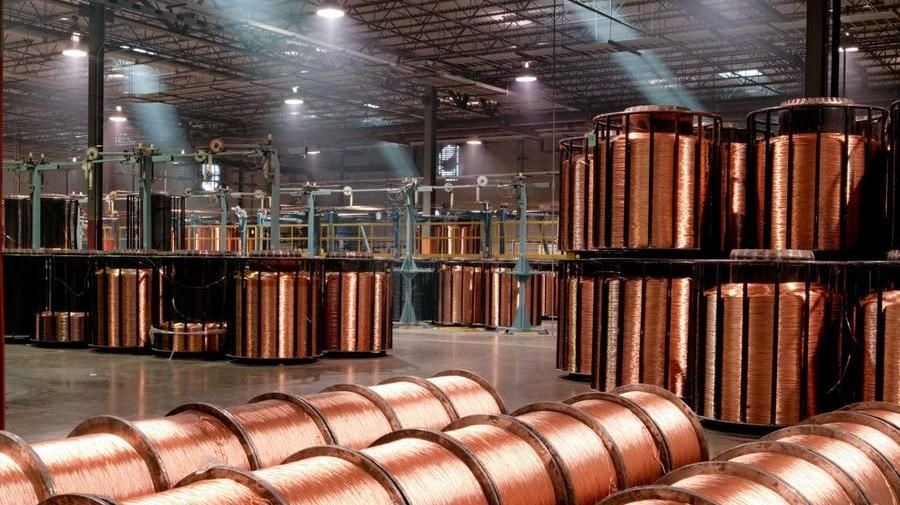

But why worry so much about lithium and copper? Thanks to its high conductivity and the ability to store energy, the huge and growing demand for the famous alkali metal is linked to the fact that it is the metal used for most batteries, from smartphones to electric vehicles and, therefore, considered extremely valuable. Thanks to its excellent thermal and electrical conductivity, copper, which is present in nature almost always in the form of minerals, has always been widely used in the production and use of electricity and in systems based on heat exchange.

After these considerations it would seem that this enormous potential has only positive feedback and therefore it represents a resource capable of ensuring prosperity and security for the country. But… is this really so? To tell you the truth, no, that’s not the case. In my opinion, there are two fundamental aspects to consider and which represent direct consequences of full-scale mining. I am speaking of the same nature and quality of the resources we are talking about, enormous, of course, but still exhaustible, and of environmental exloitation and pollution. Aside from the normal slowdowns in mining due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the expected rise in the price of copper following the growth in its demand from the automotive and renewable energy sectors, the keystones around which the supply of the metal revolves are represented by its availability in nature and by its degree or concentration. The enormous availability of the metal does not seem to worry the big mining companies operating in the northern territory, responsible for a production that, despite a continuous decrease during the pandemic period, have maintained a steady pace of work. On the other hand, what represents a problem is the degree of the metal recorded in various mining realities, which has decreased from 1 to 0.6-0.7% in recent years. This reduction is synonymous with an increase in the production costs of refined copper and causes a lengthening of the production process and therefore, an offer that is increasingly lagging behind the market schedule. A general qualitative aging of Chilean open pit mines that feel increasingly forced to operate in depth and underground.

The hope and forecasts of the mining companies find safety in the enormous availability of the precious metal and in the use of better production techniques that can guarantee a growing production and are therefore able to compensate for this qualitative deficit.

The environmental implication also remains to be considered, a direct consequence of mining, especially in the case of lithium. For decades, Chile has found itself between two ancient challengers: economic interest and environmental protection. The environmental issue lies in the locations chosen for the extraction of the alkali metal, which often belong to natural reserves or natural parks of indescribable scenic beauty and which therefore represent or can represent extraordinary and unique tourist destinations in the world. The realities subject to extraction are often the famous salares, the great salt lakes that characterize the area of the so-called “Norte Grande”, the northernmost Chilean region, in the heart of the Atacama desert, as well as in many areas occupied by natural reserves close to the great Chilean desert, in Bolivian or Argentine territory.

Salar de Atacama

Apart from the relative simplicity of the production of the famous alkali metal, either through mining or through “salt brine”, the ruthless extraction activity has two direct environmental consequences, harmful collateral damage both for the environment and for the local indigenous population that have represented a valid bulwark against environmental exploitation for decades. I am referring to the enormous quantities of CO2 produced and to the evaporation of water on site, a resource of primary importance for the indigenous agro-pastoral communities of the great altiplano and in general for the entire Chilean population concentrated in the northern region. The water in the underground salt lakes is brought to the surface and evaporated in large tanks, an operation that represents a first part of the production process and which has led to a gradual damage to the salt lakes over the decades, causing a progressive drying up of their wetlands areas at the edges of large salt flats, as well as local rivers and aquifers. Indiscriminate water extraction directly affects communities that face serious water supply problems for agriculture, pastoralism and local tourism, leading to the emergence of conflicts and social instability.

According to studies by the University of Antofagasta in Chile, two million liters of water are needed for every ton of extracted mineral, which has remained underground for millions of years.

The intense extraction activity is therefore the cause of serious water and social imbalances and hypothesizing a solution to this context is not simple at all. Although the issue is well known at a legal and governmental level, the first and only realities to actively fight against the phenomenon are, as already mentioned, the different indigenous communities that live in the great desert of Atacama, Atacameños, Lickanantay, Colla, Quechua and Aymara , realities sensitive to the phenomenon and who, like me, feel responsible and obliged to spread the true nature of mining and quarrying realities that are active in this natural paradise, in the great hope that a greener and better solution is proposed and soon reached for everyone.

0 Comments